I have been learning to use colored pencils this year–Laura’s idea really. She and I bought matching sets of pencils and two drawing journals. We spent many winter nights drawing before bedtime. As is usual with any new drawing practice, this has changed my way of seeing the world. When you try to accurately reproduce colors you notice both their simplicity and their complexity. All the shades we see are combinations of the primary colors, red, yellow and blue. Yet variety of secondary hues is infinite. That said, some are more common than others, which is demonstrated by the fact that you can find them in your pencil set–dark green, grass green, violet blue, sky blue, crimson red, sienna brown, etc. Becoming acquainted with these different pencils gives you a kind of visual vocabulary which you begin to apply to the world around you. You notice shades all around you because you can name them, or at least associate them with the pencils you’ve been using. Colors become objects to you. This is in accord with George Herbert Mead’s central principle: it is our attention that creates the object, through selection and manipulation. Not to say that the world is a creation of the mind (Mead was a Darwinist, not an Idealist), but rather that until we notice a particular aspect of the world it isn’t a thing to us. We become aware of an object because it impinges on our attention for some reason (threat or pleasure) and having encountered it we continue to select it out from the perceptual welter for our human purposes.

The image below is of a copperhead snake (Agkistrodon contortrix). I drew it because I am making a chapbook out of a trio of poems by the Kansas poet Steven Hind, and one of his poems takes as its subject a youthful encounter with a copperhead in a hayfield. I drew the snake from a picture I found on the internet, but the subject does have a personal connection to me. When I was a boy my mother and I went walking down to the cattle pond on her father’s farm. It had been a bad year for snakes and she took along a .22 rifle (not a usual action for her–in fact I never saw her do it again). As we walked along the bank she spotted a copperhead and swung the rifle barrel up and shot it. I was of course impressed. I remember us examining the snake, poking its colorful body with a stick.

Here is the poem:

Baling After the Flood We catch the cottonmouth sliding under August for water and shade. We fling the hatchet at his tense aim, and kill him. The stubble whispers with his writhing. We insist our fingers touch the dead vigor. We twist open the white jaws, clutching revulsion by the throat. These thin teeth, we say. All day our hands tremble in the hot grip of work.

I like the poem, and I like my drawing. I like the fact that the one is not narratively connected to the other. Rather, the drawing captures the ornate splendor of the snake, which is not really described in the poem, except perhaps in the word “vigor.” In the chapbook I am creating the drawing doesn’t sit beside the text but comes after it, as a surprise for the reader. The snake seems alive on its own terms. It is not reducible to a threat or a symbol of evil.

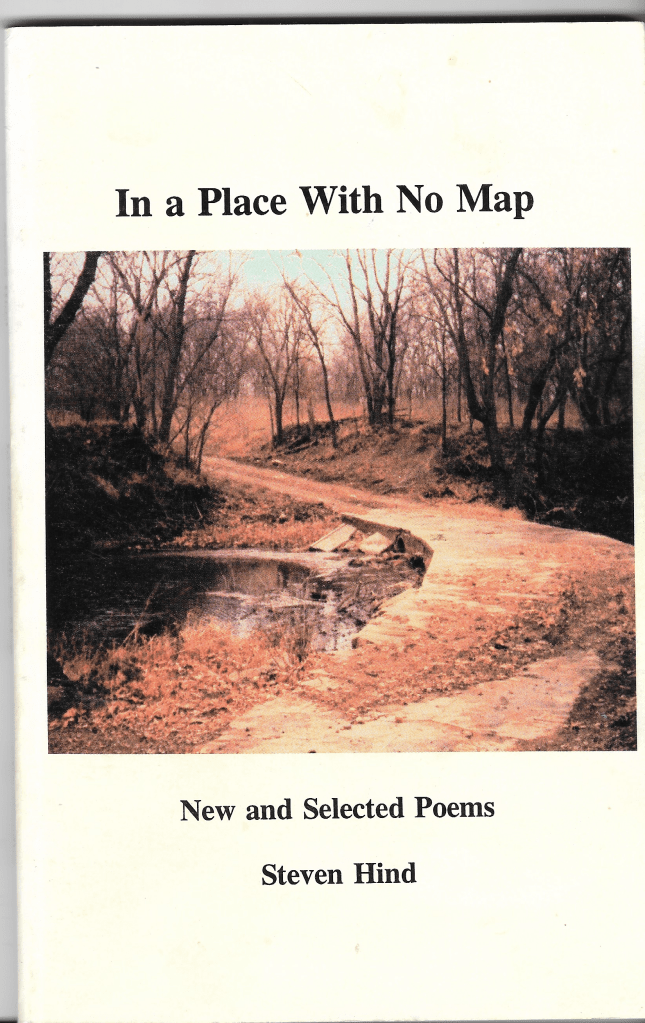

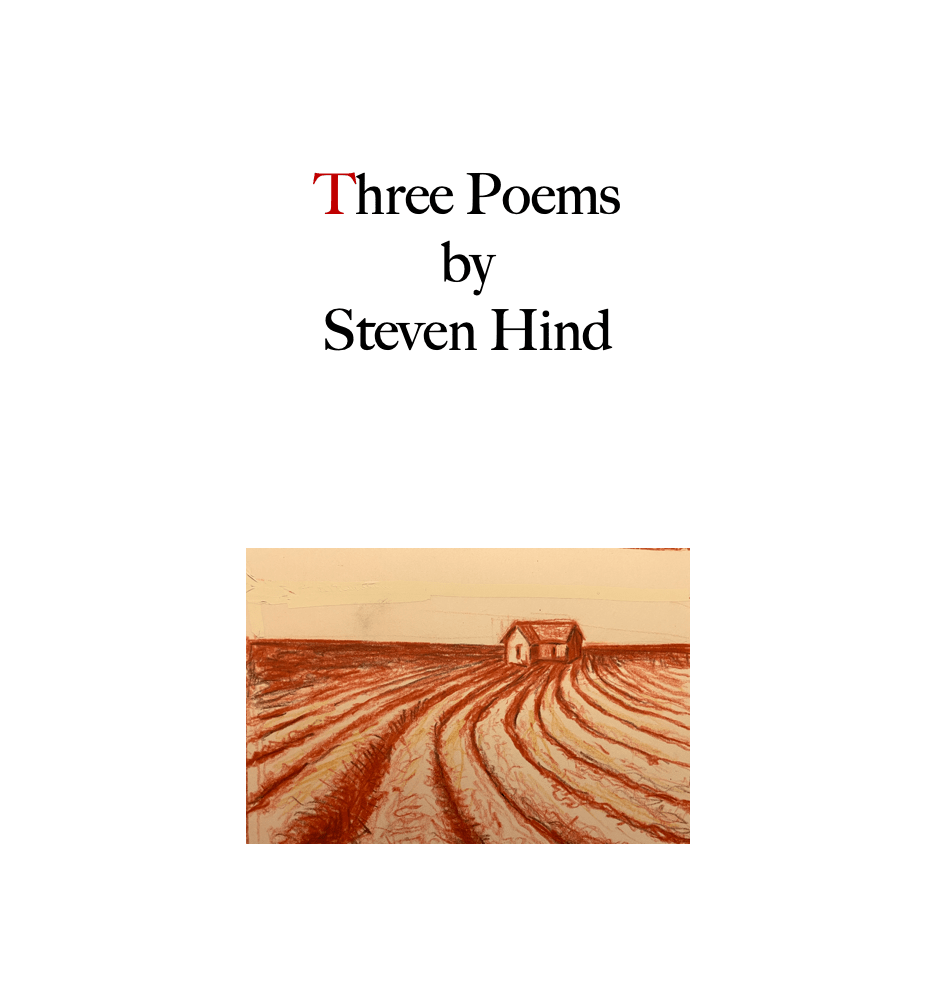

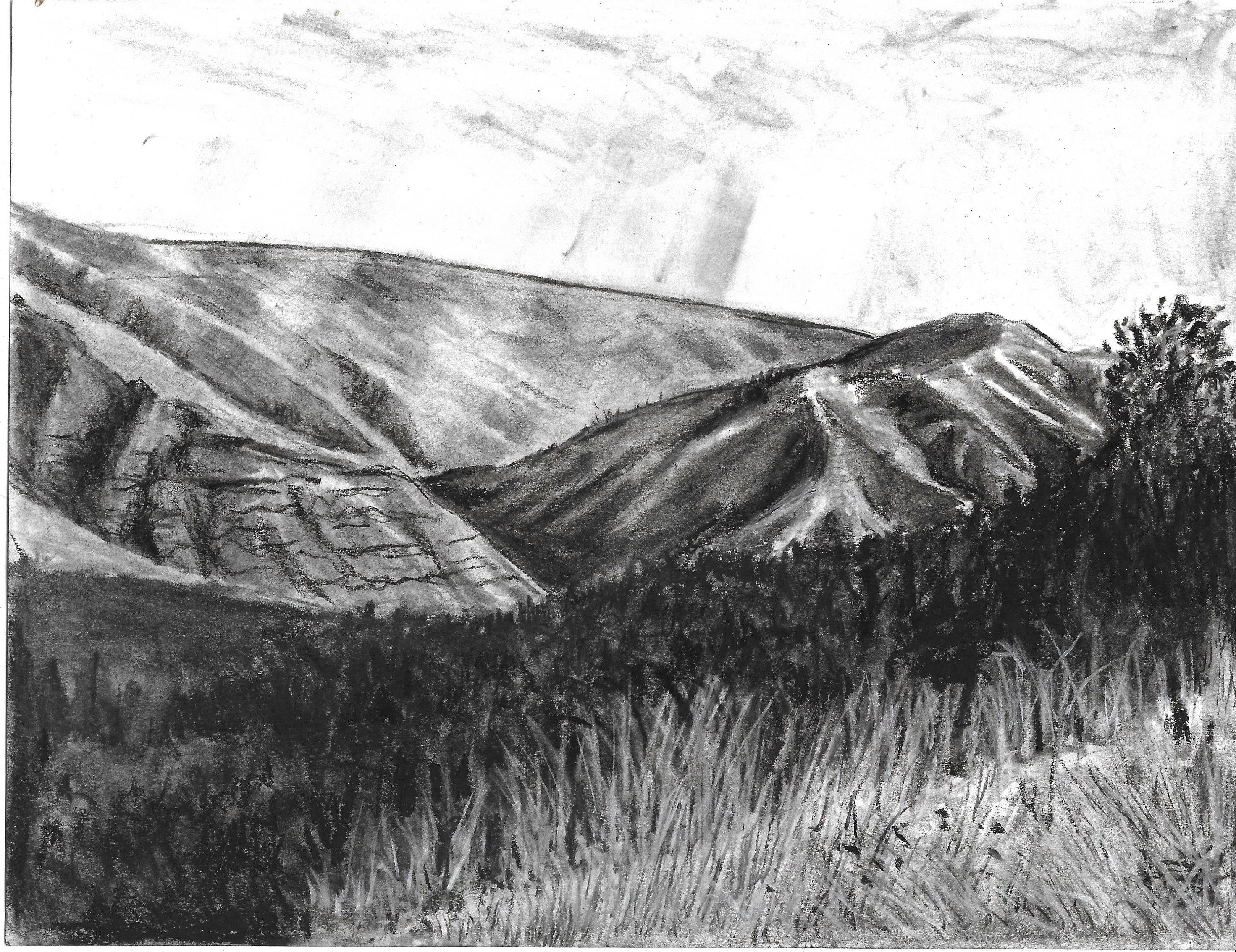

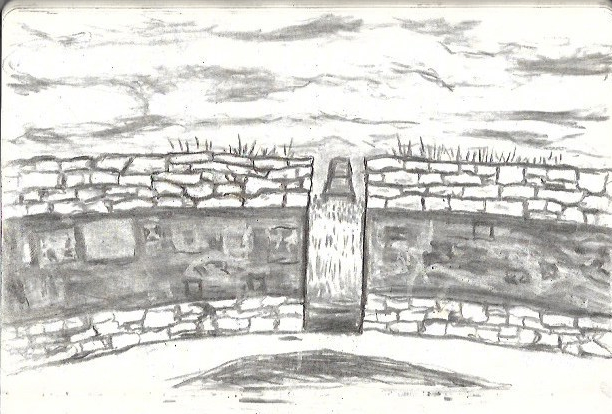

How did I get started on this project of creating drawings to go with poems? I was reading Steven Hind’s book In a Place With No Map. I liked how the poems evoked the powerful feelings Hind has for the Kansas landscape. Then I got interested in the cover of the book(see below). The cover seemed awkward–too much white overall, and the photo was grainy and unattractive, like a faded Kodachrome. But on the other hand it was strangely interesting.

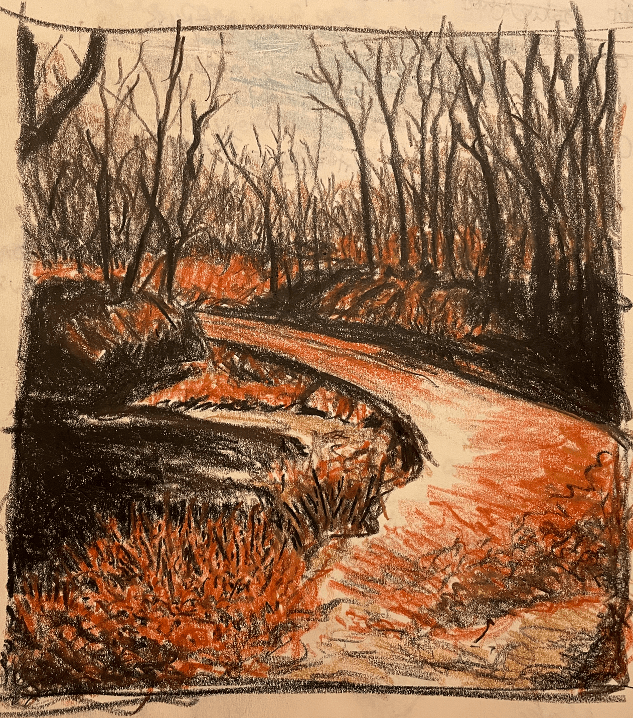

I noticed that the range of colors matched my pencils, so I tried doing a drawing of it. When I was finished I felt that I had reproduced the feeling the photo gave me. The fact that I had turned the photo into a drawing made the image more subjective and, to my mind, augmented the mystery and even vague dread in the composition:

I really like the Sanguine pencil in this. Once I had finished the drawing, I decided to go ahead and pair it with a poem from the book. I tried out many different ones, but finally settled on the titular poem, “In a Place With No Map.”

In a Place With No Map When the far path plays out, you know you are getting somewhere: home between sky and stone. Shade your own steps as you make trail. You are the one the wind has moaned for a thousand years. You are calm, claiming your kingdom a random way through the grass where the land says, Because you love me, your job is to stay with the world.

I think the drawing picks up on the contrast between love and moaning, between getting lost and getting somewhere (implying that they can be the same thing). I decided I needed to find a couple of other poems that spoke to this theme of “claiming your kingdom” and finding a way to stay in the world. I chose on “Baling After the Flood” because it seemed to offer resistance to the idea that the world is always welcoming. A world with cottonmouth snakes in it is hard to love, even if it is also splendid. Loving the world is a “job” because the world contains paradoxical situations.

The other poem I chose was this one:

Her Coyote Dream I wanted to crawl into her den and become a part of that place, she said. I resented my car back there on the road, giving me away. I lay in the sweet grass watching that hole where the big female disappeared into the earth, and the wind assembled a chorus of grasses to make me believe I was at one with the land. I wanted more than anything every in my life to enter and belong.

If “In a Place With No Map,” speaks of choosing to love the world and “Baling After the Flood” shows that same world to be threatening, this third poem describes a person’s wish to “enter and belong.” This echos the idea of “claiming the kingdom,” but the poem’s subject, an unnamed woman, narrates that project in a way that depicts it as on some level thwarted. The implication of her story is that we are barred from complete union. We can’t go down the hole with the coyote.

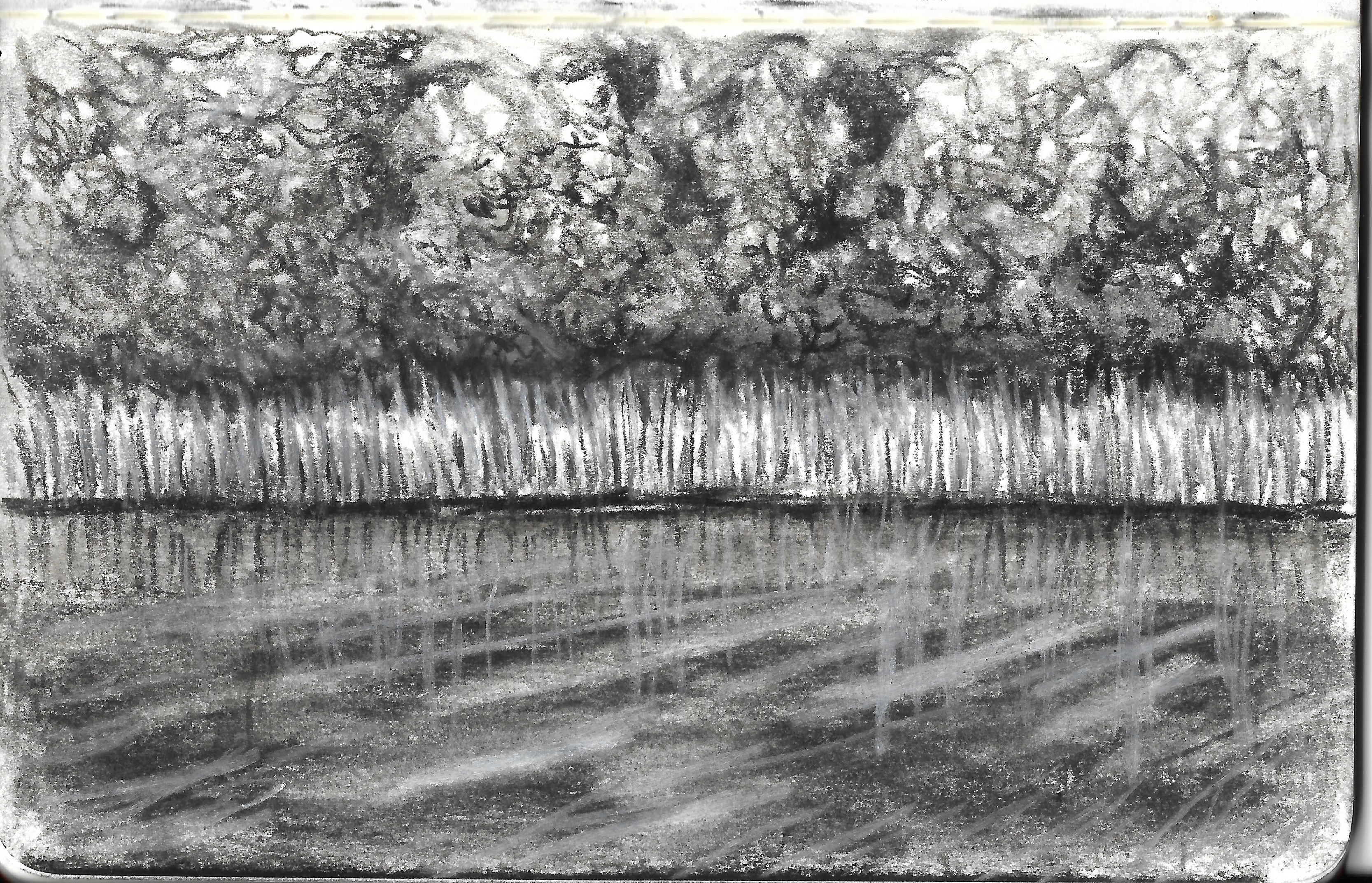

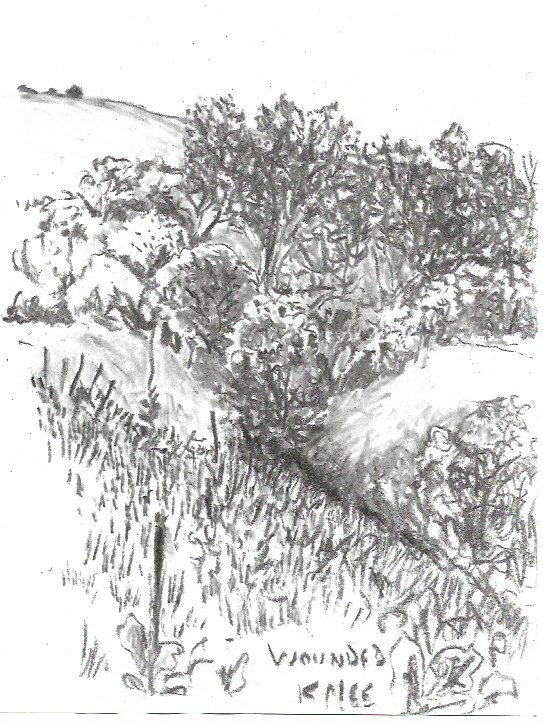

When you put the three poems together they create a dialogue. I wanted a third drawing that might do the same. I was unfamiliar with coyote dens, but the internet provided a wealth of examples. I chose one of them and used my limited palette of Derwent pencils to create the feel of a dry stream bed in wintertime. Again, the image contains little of the narrative detail of the poem, but tries to echo the poem’s sense of the den as an alluring space, fringed by a “chorus” of grasses. (As an aside, I used a technique I saw on an online tutorial: I scratched the paper with a knife so that when I laid down the black pencil to make the mouth of the cave, the cuts in the paper remained white–a fine detail often used for the whiskers of animals).

In this image, I feel that the first person narration of the woman is replaced by the point of view of the person looking at the drawing. That is, we don’t see the woman or her car, but we see, perhaps, what she sees. An entrance, obscured in darkness.

The last stage of my project was designing the chapbook. I chose Big Caslon typeface (my favorite) and laid out the poems so that they would each stand on their own: that is, each poem is set on the recto page with a blank page on the verso side to give the poem lots of room to breathe. The image comes after you turn the page, and is similarly isolated (this also makes sure the highly colorful images don’t bleed through, though I am also using a heavyweight paper). Image and text are given equal weight, but the image follows the text to prevent the reader from pre-imagining the poem. I wanted the poem to speak first, and the image to respond, after a beat.

I did do one more drawing, for the title page of the book. I needed something suitably “Kansan” so I took as my inspiration a Depression-era photo of a dustbowl farm. I did it entirely with sanguine. I felt this echoed the snake and the landscape drawing and also “bloodied” the landscape, giving it a sense of threat and vitality that the original black and white photo did not have.

I ended up using a similar red for the first letter in both the book title and the individual poem titles. I am happy with the result.

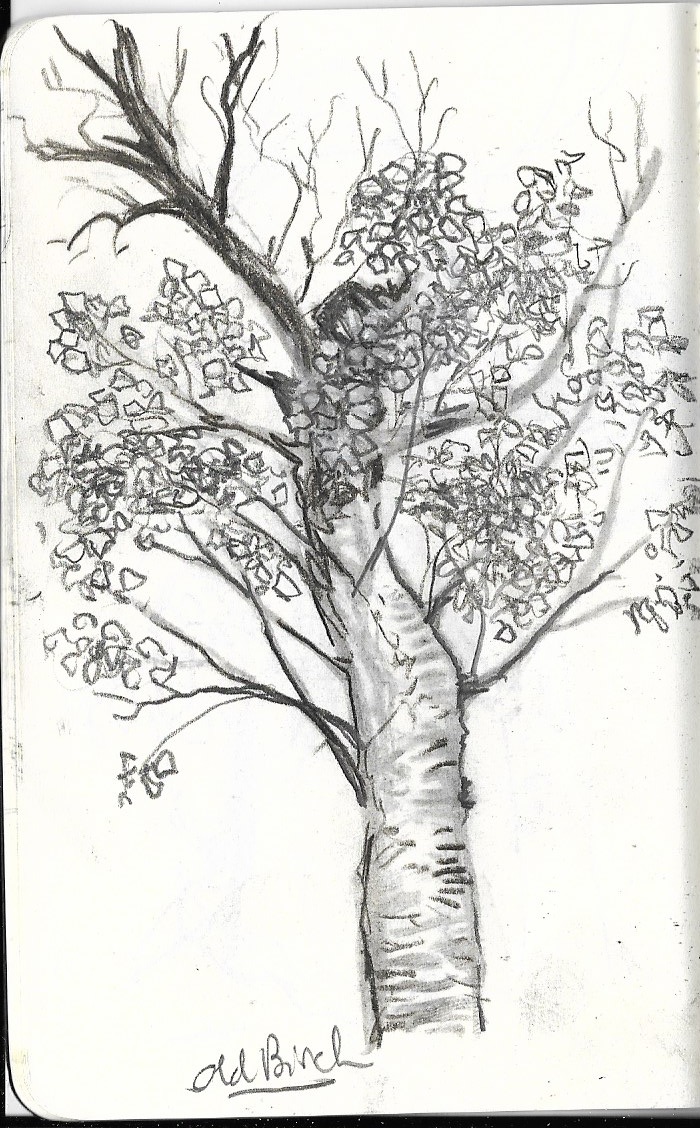

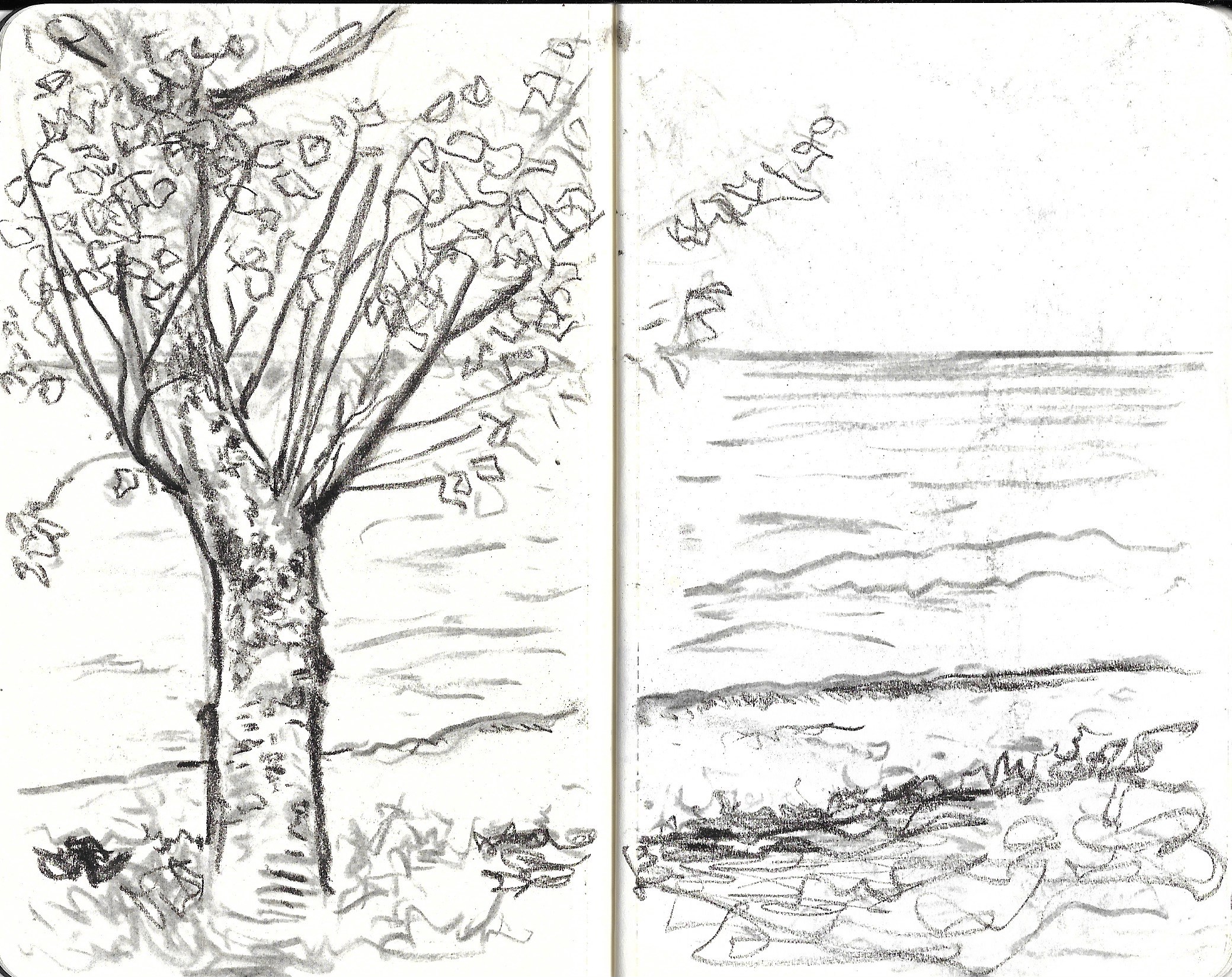

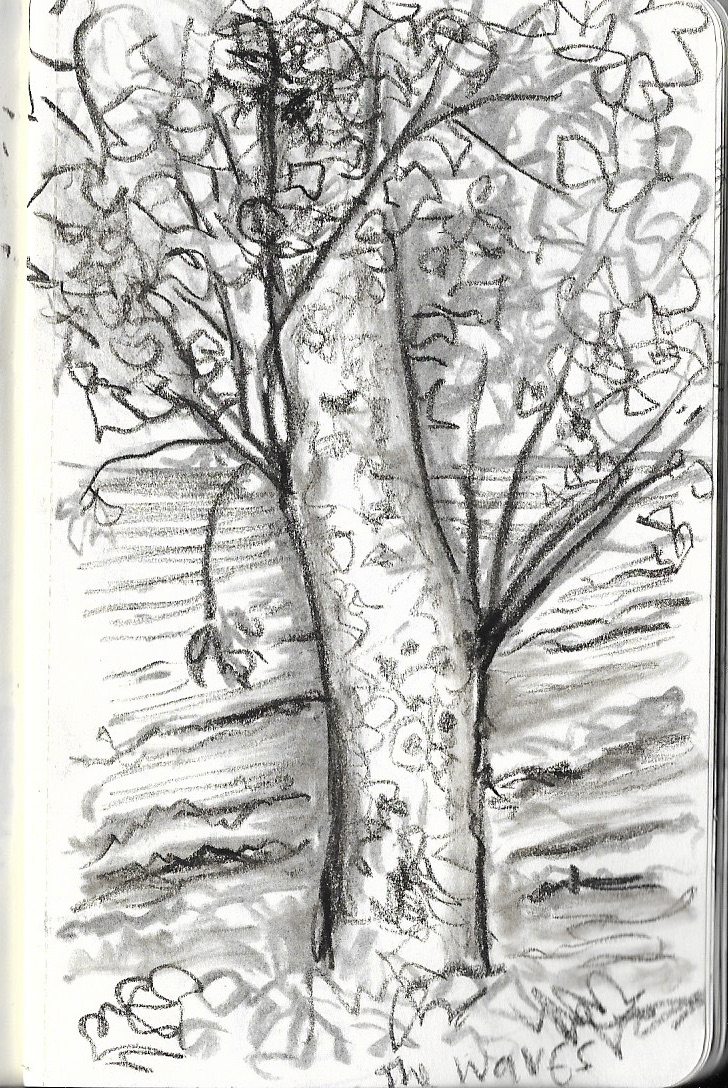

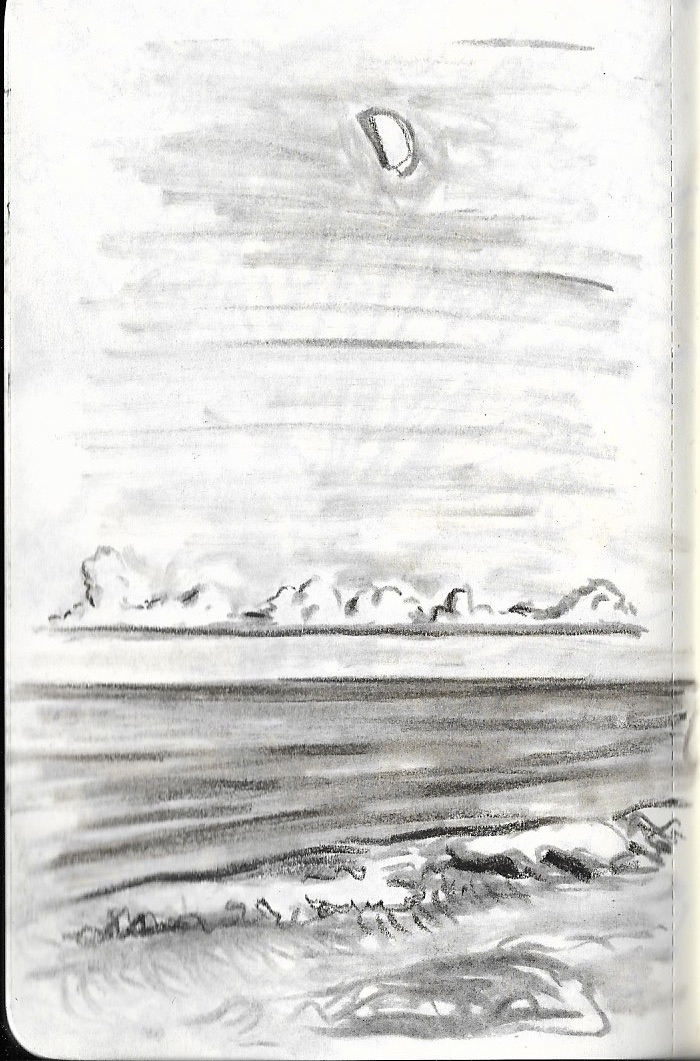

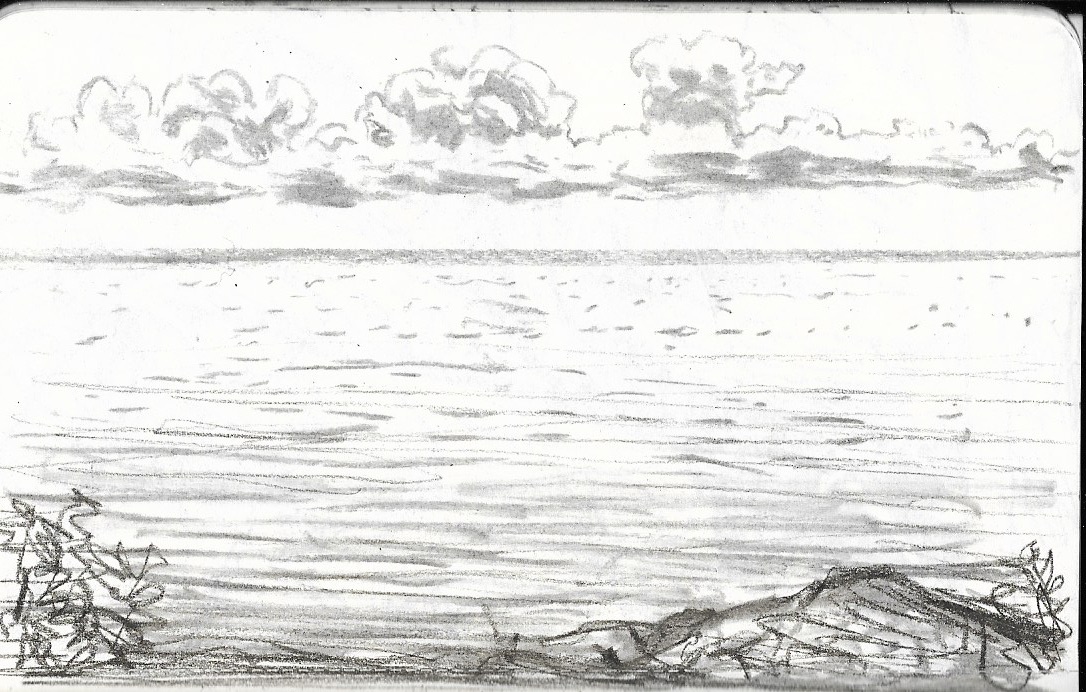

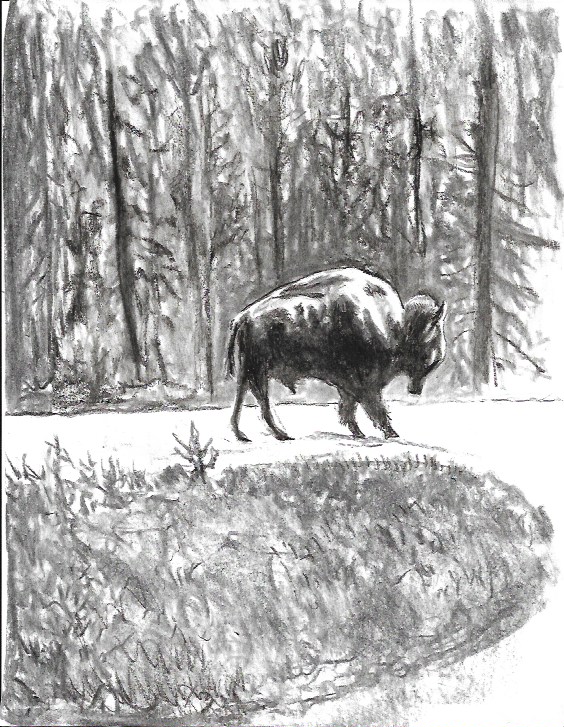

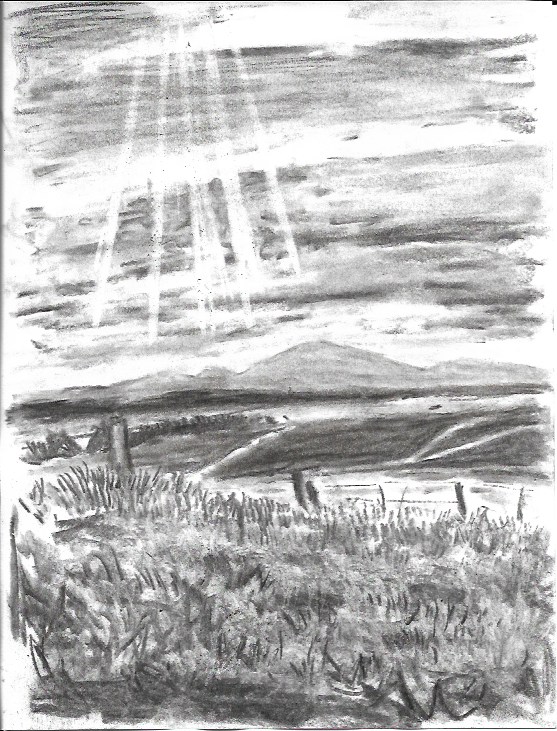

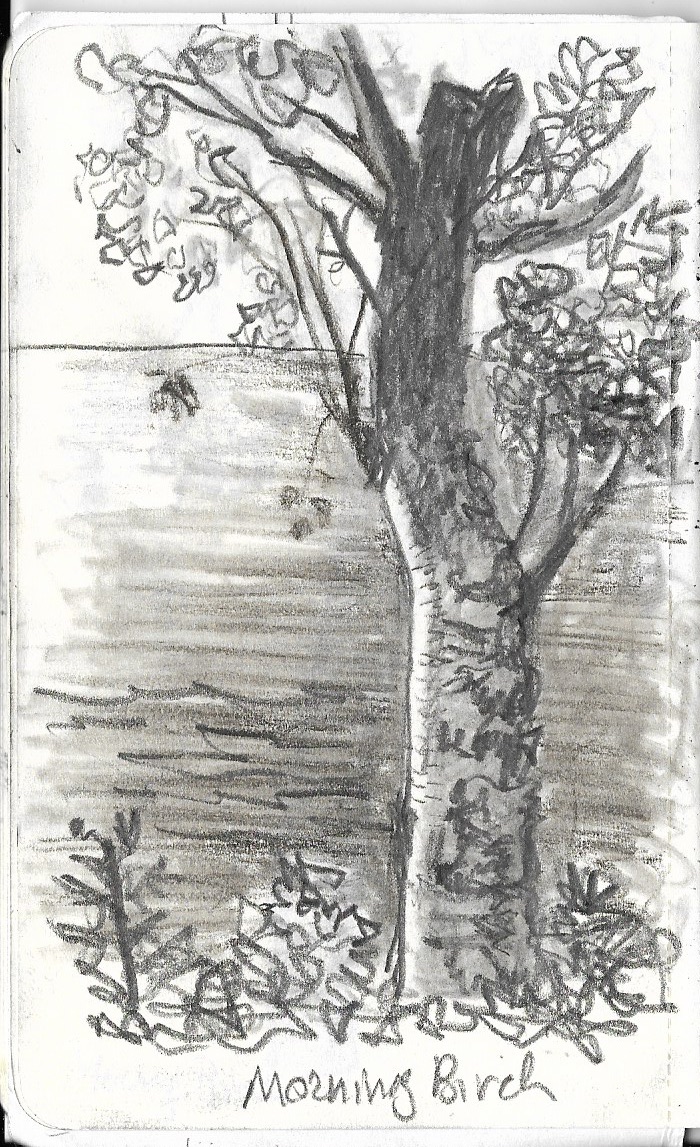

The sense of immediacy in my resulting sketches seemed palpable. But how to explain this? What did speed have to do with it? And was the crudeness of the medium–I was literally drawing with a burnt stick–an asset?

The sense of immediacy in my resulting sketches seemed palpable. But how to explain this? What did speed have to do with it? And was the crudeness of the medium–I was literally drawing with a burnt stick–an asset?